This post is based on research from “Adapting Social Spam Infrastructure for Political Censorship” published in LEET 2012 – a pdf is available under my publications. Any views or opinions discussed herein are my own.

In recent years social networks have emerged as a significant tool for both political discussion and dissent. Salient examples include the use of Twitter for a town hall with the Whitehouse. The Arab Spring that swept over the Middle-East also embraced Twitter and Facebook as a tool for organization, while Mexicans have adopted social media as a means to communicate about violence at the hands of drug cartels in the absence of official news reports. Yet, the response to the growing importance of social networks in some countries has been chilling, with the United Kingdom threatening to ban users from Facebook and Twitter in response to rioting in London and Egypt blacking out Internet and cell phone coverage during its political upheaval. While nation states can exert their control over Internet access to outright block connections to social media, parties without such capabilities may still desire to control political expression.

Recently, I had a chance to retroactively examine an attack that occurred on Twitter surrounding the Russian parliamentary elections. For a little back story on the attack, upon the announcement of the Russian election results, accusations of fraud quickly followed and protesters organized at Moscow’s Triumfalnaya Square. When discussions of the election results cropped up on Twitter, a wave of bots swarmed the hashtags that legitimate users were using to communicate in an attempt to control the conversation and stifle search results related to the election.

In total, there were 46,846 Twitter accounts discussing the election results. It turns out, 25,860 of these were controlled by attackers in order to send 440,793 misleading or nonsensical tweets, effectively shutting down conversations about the election. While abusing social networks for political motives is nothing new, the attack is noteworthy because (1) it relied on fraudulent accounts purchased from spam-as-a-service marketplaces and (2) it relied on over 10,000 compromised hosts located around the globe. These marketplaces — such as hxxp://buyaccs.com/ — are traditionally used to outfit spam campaigns, freeing spammers from registering accounts in exchange for a small fee. However, this attack shows that malicious parties can easily adapt these services for other forms of attacks, including political censorship and astroturfing.

Below is a preview of our results. For more details, check out the full LEET 2012 paper.

Tweets

We identify 20 hashtags that correspond with the Russian election, the top 10 of which are shown below.

| Hashtag | Translation | Accounts |

| чп | Catastrophe | 23,301 |

| 6дек | December 6th | 18,174 |

| 5дек | December 5th | 15,943 |

| выборы | Election | 15,082 |

| митинг | Rally | 13,479 |

| триумфальная | Triumphal | 10,816 |

| победазанами | Victory will be ours | 10,380 |

| 5dec | December 5th | 8,743 |

| навальный | Alexey Navalny | 8,256 |

| ridus | Ridus | 6,116 |

We aggregate all of the accounts that participated in the hashtags and then segment them into accounts that are now suspended by Twitter (25,860) and those that appear to be legitimate (20,986). We then aggregate all of the tweets sent by these accounts during the attack. As shown in the following figure, legitimate conversations (black line) appear diurnally over the course of 2 days from December 5th — December 6th. Conversely, the attack (blue line) occurs in two distinct waves, outproducing tweets compared to legitimate users at certain periods.

If we restrict our analysis to only tweets with the relevant election hashtags, the impact of the attack is even starker.

Accounts

One of the most interesting aspects of the attack was the accounts involved. Accounts were registered in four distinct waves, where each wave has a uniquely formatted account profile that can be captured by a regular expression. We call these waves Type-1 through Type-4. Accounts were acquired as far back as seven months proceeding the attack. For most of the time, the accounts were dormant, though some did come alive at various intervals to tweet politically-orientated tweets prior to the attack.

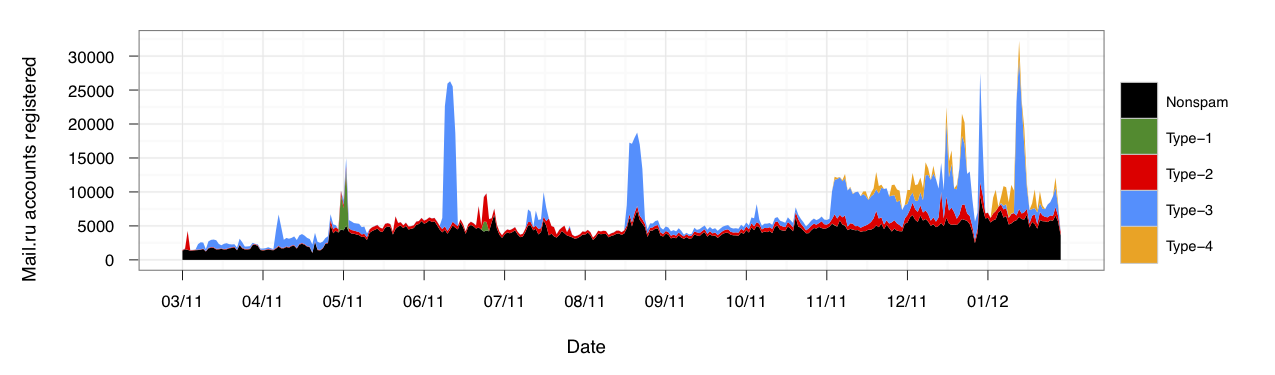

Interestingly, all of the accounts were registered with mail.ru email addresses, which allows us to extend our analysis one step further. We take the regular expressions that capture the accounts used in the attack and apply it to all Twitter accounts registered with mail.ru emails in the last year. From this, we identify roughly 975,000 other spam accounts, 80% of which remain dormant with 0 following, 0 followers, and 0 tweets. These accounts were registered in disparate bursts over time and likely all belong to a single spam-as-a-service program. The registration times of these presumed spam accounts are shown below. Legitimate accounts show a relative trend in growth, while the anomalous bursts in registrations are attributed to a malicious party registering accounts to later sell.

IP Addresses

We examine one final aspect of the attack: the geolocation of IPs used to access accounts tweeting about the election. Legitimate accounts tend to be accessed from either the United States (20%) or Russia (56%). In contrast, the accounts controlled by the attacker were accessed from hosts located around the globe; only 1% of logins originated from Russia. Furthermore, 39% of these IP addresses appear in blacklists, indicating many of the hosts are used simultaneously in other spam-related activities. Combined, this information reveals that the attackers relied on compromised hosts which again may have been purchased from the spam-as-a-service underground.

|

|

One Comment

Comments are closed.